Vladslo’s Echoes of Grief:

Käthe Kollwitz’s “The Grieving Parents”

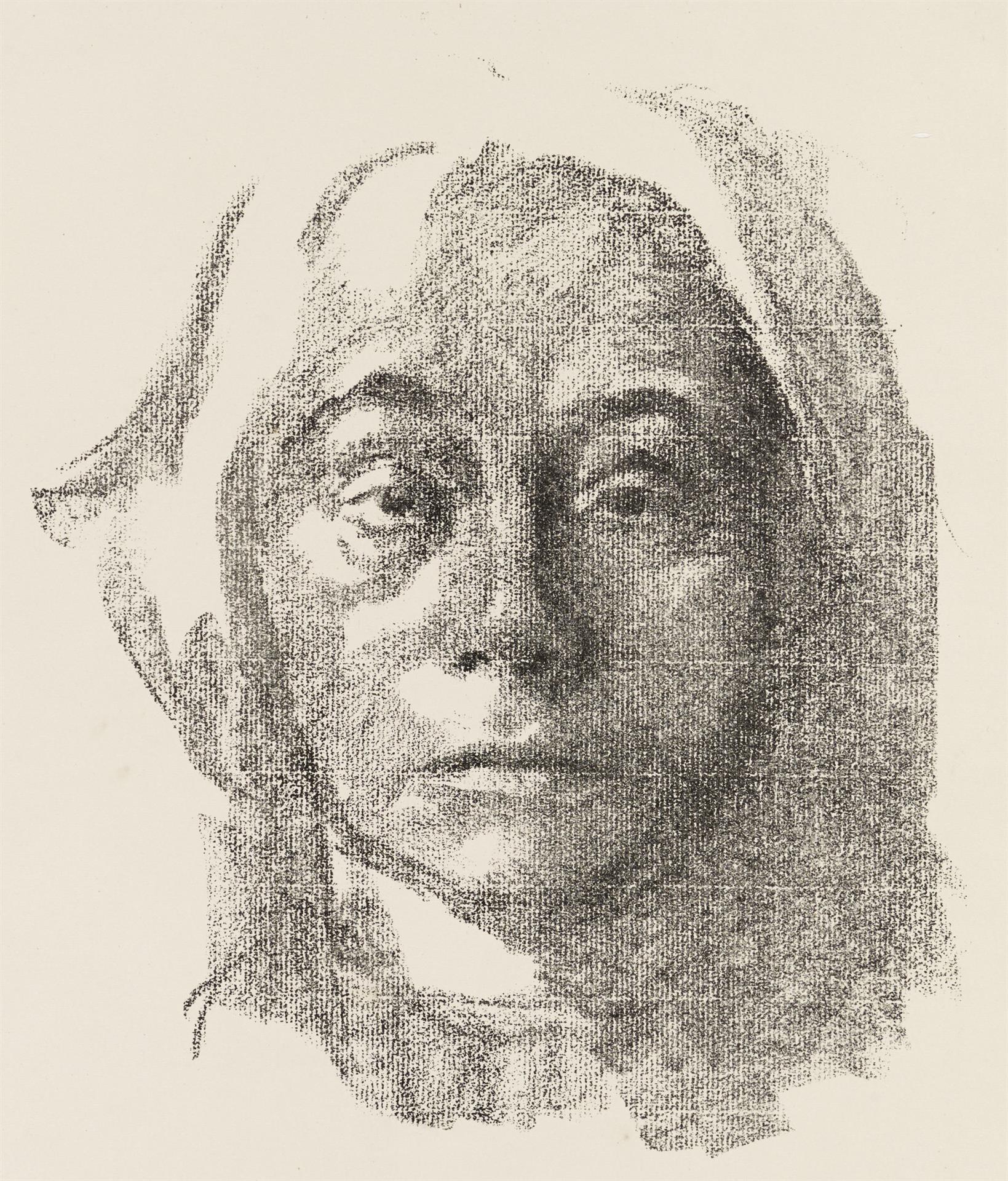

In Vladslo German Military Cemetery, you are always aware of the presence of the “Grieving Parents.” No matter where you are in this vast cemetery, there is always a direct line of sight to them. The figures—one man and one woman—are larger than life. Carved from Belgian granite, a grey-bluish limestone, they kneel on rough block plinths.

Though they are together, there is a profound sense of separation in their grief. Their sorrow is uniquely their own. Is this what Käthe Kollwitz is trying to convey? That the parents of a deceased child cannot find comfort in sharing the burden of their loss? Each parent struggles individually with their own battle of grief, making their sorrow distinctly personal.

This distinct grieving process is further emphasised in the stances of the two figures. The father kneels upright, while the mother bows her head. Both have their arms wrapped around themselves, as if resisting a chilling wind. Yet, could it be that they are clutching the broken hearts of their sorrow—the deep emptiness that accompanies loss?

The artistic legacy of Käthe Kollwitz is profoundly intertwined with the personal tragedies she endured, particularly the loss of her son Peter in World War I. Her diaries and letters, alongside her powerful sculpture The Grieving Parents (also known as The Mourning Parents or The Parents), offer an unparalleled window into the human cost of war and the enduring nature of grief.

Käthe Kollwitz, a prominent German artist, initially held a complex and somewhat supportive stance towards Germany’s involvement in World War I in 1914, believing the nation was pushed into the conflict and had a duty to defend itself. This initial perspective, however, dramatically shifted as the war progressed and she experienced profound personal loss.

Kollwitz’s early diary entries and later reflections provide evidence of her initial belief that Germany was compelled into the war. On September 30, 1914, she wrote in her journal, “Nothing is real but the frightfulness of this state, which we almost grow used to. In such times, it seems so stupid that the boys must go to war. The whole thing is so ghastly and insane. Occasionally, there comes that foolish thought: how can they possibly take part in such madness? And at once the cold shower: they must, must!”.

This entry reveals a sense of inevitability and a perceived obligation for young men to participate, suggesting an acceptance, albeit a reluctant one, of the war’s necessity. Her support for the war effort was also evident in her initial willingness to allow her youngest son, Peter, to enlist as a volunteer. She later reflected on this decision, stating, “It was, she recalled, ‘this sacrifice to which [Peter] tore me and to which we tore Karl’”. This indicates that she, along with her husband, consented to Peter joining the army, driven by a belief in Germany’s defensive posture.

This initial support stemmed from a widespread conviction among many Germans, including Kollwitz, that Germany was fighting a defensive war. She believed that “Germany was in the right and had the duty to defend herself”. This sentiment was common at the war’s outset, as propaganda and nationalistic fervour painted the conflict as a necessary defence of the homeland. However, the devastating impact of the war, particularly the death of her son Peter in October 1914, profoundly altered her views.

Her art and writings thereafter became powerful expressions of pacifism and anti-war sentiment, reflecting her deep sorrow and a growing disillusionment with the conflict. She later expressed a feeling of betrayal regarding the initial justification for the war, stating in March 1918, “The feeling that we were betrayed then, at the beginning. And perhaps Peter would still be living had it not been for this terrible betrayal. Peter and millions, many millions of other boys. All betrayed”. This stark shift highlights her initial, albeit misguided, belief in the war’s necessity and her subsequent realisation of its tragic and unnecessary human cost.

The Artist’s Son: Peter Kollwitz’s Brief Life

Peter Kollwitz was born on February 6, 1896, in Berlin, Germany, to the renowned artist Käthe Kollwitz and physician Karl Kollwitz. He was the younger of two sons; his older brother was Hans Kollwitz. Peter spent most of his life at the family home located at Weissenburger Strasse 25 (now Kollwitzstrasse 56a) in the Prenzlauer Berg district of Berlin, where his father’s medical practice and occasionally his mother’s studio were also situated.

Peter’s youth was marked by artistic inclination, intellectual curiosity, and active participation in the emerging German youth movement. His room reflected his varied interests, featuring an iron bed frame, a cupboard filled with a rock collection, a plaster head of Narcissus, a bookcase, and an easel. He also had a framed silhouette of his profile, a guitar, skis, and a toboggan.

Käthe Kollwitz’s diary entries reveal Peter’s diverse passions, which included playing billiards, rock climbing, expressionistic painting, reading “Zarathustra,” stargazing, visiting Tuscany, and participating in mass demonstrations against the threat of war. He was known to read Oscar Wilde in English, smoke, and occasionally rebel against school.

Beginning in 1908, Peter contributed to a student newspaper project called “Der Anfang” (The Beginning), submitting drawings and texts. This publication later featured contributions from notable figures such as Walter Benjamin, Siegfried Bernfeld, and Gustav Wyneken. Through his “foster brother” Georg Gretor, Peter became involved in the “Wandervogel” youth movement, which promoted self-organised hikes and trips. He developed a close friendship with Erich Krems, another member of the movement.

In April 1911, Peter expressed his desire to become an artist, specifically a painter. His mother showed some of his drawings to Max Liebermann, who recognised his talent and advised him to enrol in an art academy or the teaching institute of the Berlin Museum of Decorative Arts. Peter left school in 1912 after obtaining his Mittlere Reife (intermediate school certificate) and subsequently attended Arthur Lewin-Funcke’s painting class at the Berlin Museum of Decorative Arts.

The outbreak of World War I in July 1914 had a profound impact on Peter’s life. While on holiday in Norway with friends, he learned of the declaration of war and, along with his companions, decided to volunteer for military service. Despite his father’s initial reluctance, Käthe Kollwitz ultimately persuaded her husband to allow Peter to enlist. At just 18 years old, Peter joined the Reserve Infantry Regiment No. 207 as a musketeer.

After several weeks of training, Peter Kollwitz was deployed to the Western Front. He was killed in action on the night of October 22/23, 1914, near Esen (Diksmuide) in West Flanders, Belgium, during the First Battle of Flanders. A friend, Hans Koch, dug his grave and later reported on the burial, noting that a cross was erected with the inscription: “Here died the heroic death for the fatherland Peter Kollwitz, war volunteer Res. Inf. Reg. 207.”

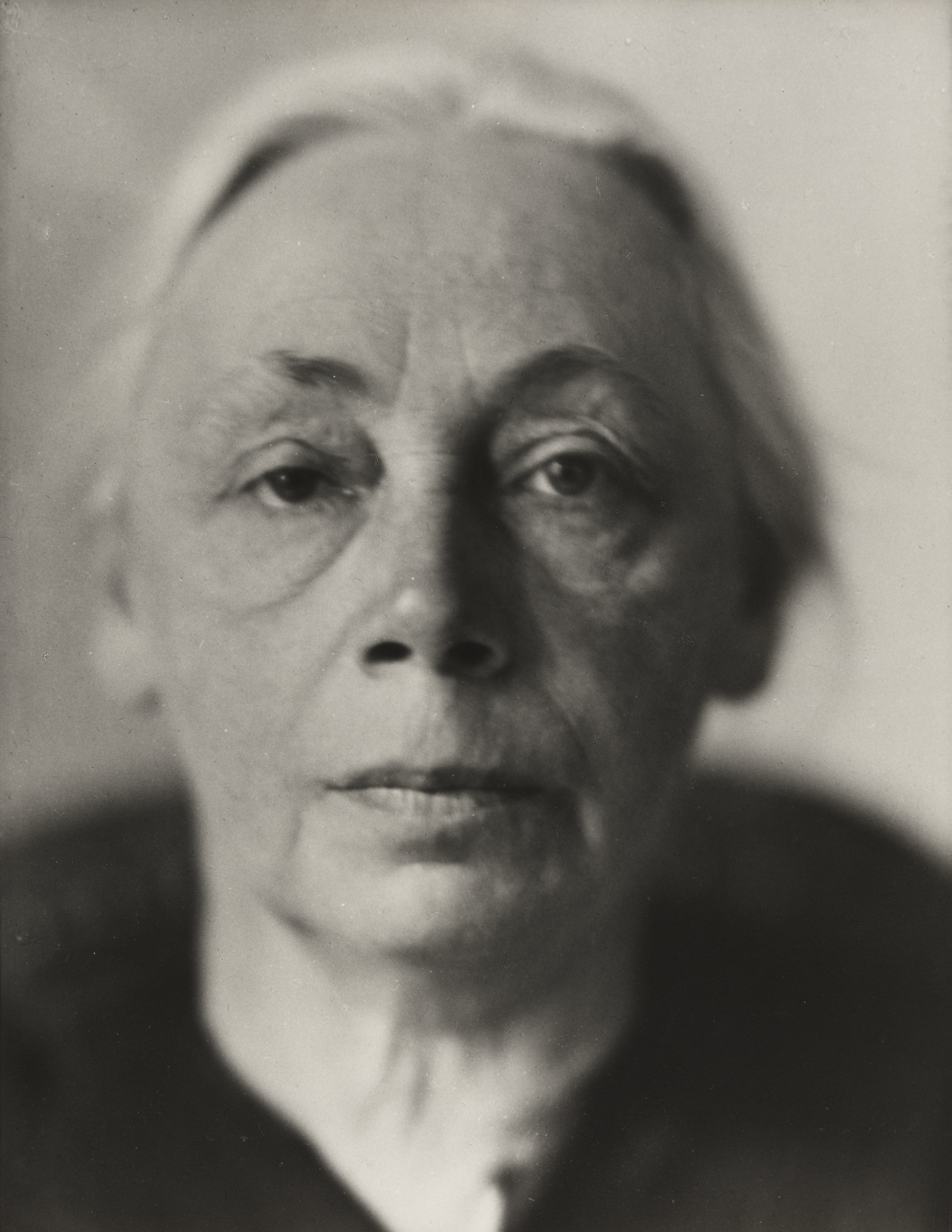

The Life and Times of Käthe Kollwitz:

A Contextual Overview

Käthe Kollwitz (1867-1945) was a German artist whose work primarily focused on themes of poverty, hunger, war, and death. Born in Königsberg, East Prussia (now Kaliningrad, Russia), she was deeply influenced by the social and political upheavals of her time. Her early artistic training emphasised drawing and printmaking, mediums she would master and use to convey powerful social commentary.

Kollwitz’s commitment to depicting the suffering of the working class and the marginalised was evident throughout her career, earning her both acclaim and controversy. Her art was never merely aesthetic; it was a vehicle for empathy and a call for social justice.

The outbreak of World War I in 1914 marked a pivotal turning point in her life and art. Her younger son, Peter, then just 18 years old, enthusiastically volunteered for military service. His death on the Western Front in October 1914, just weeks after enlisting, shattered Kollwitz and her family. This personal catastrophe would forever shape her artistic output, transforming her from a social commentator into a profound chronicler of grief and loss.

The war, which claimed millions of lives, was not an abstract concept for Kollwitz; it was a deeply personal wound that never truly healed. Her art became a testament to this enduring pain, a universal expression of the human cost of conflict.

The political climate in Germany between the wars, including the rise of Nazism, further impacted Kollwitz. Her pacifist stance and her art, which often depicted suffering and challenged nationalistic fervour, put her at odds with the regime. She was forced to resign from her position at the Prussian Academy of Arts in 1933, and her work was deemed “degenerate art” by the Nazis.

Her work was removed from museums, and she was banned from exhibiting. In 1936, she and her husband were visited by the Gestapo and threatened with arrest and deportation to a concentration camp, though no further action was taken due to her international renown.

Despite these hardships, she remained committed to creating art, driven by a deep dedication to truth and human dignity. Her death occurred shortly before the end of World War II in 1945, following a period marked by significant personal loss and displacement. After her home in Berlin was bombed in 1943, she was evacuated and lost many of her drawings, prints, and documents. She first relocated to Nordhausen and then to Moritzburg, where she spent her final months as a guest of Prince Ernst Heinrich of Saxony.

Käthe Kollwitz endured immense personal suffering throughout her life. With her son Peter killed in October 1914, her husband Karl passed away in 1940, and her grandson, also named Peter, died on the Eastern Front in 1942. Käthe Kollwitz transformed her immense personal suffering into a legacy of art that resonates with profound humanity and raw honesty.

The Diary and Letters:

A Chronicle of Grief and Artistic Process

Käthe Kollwitz’s diaries and letters are invaluable primary sources that offer an intimate glimpse into her emotional landscape and artistic struggles, particularly in the aftermath of Peter’s death. Her entries are not merely factual records but deeply personal reflections on grief, despair, and the search for meaning in the face of unimaginable loss. The raw honesty of her writing reveals the profound impact of Peter’s death on her psyche and her artistic process.

In an entry from December 1914, just two months after Peter’s death, Kollwitz wrote: “There is only one thing that matters: to live through it, to live through it to the end.” This sentiment encapsulates her determination to confront her grief head-on, rather than succumb to it. Her diaries reveal a prolonged and arduous mourning process, spanning years, during which she grappled with feelings of guilt, anger, and profound sadness. She questioned the purpose of life and art in a world ravaged by war. In a letter to her friend, the poet Rainer Maria Rilke, she confessed, “My work is now only a reflection of my pain.” This statement highlights how deeply intertwined her personal suffering became with her artistic output.

“That point in time marked the beginning of old age, my walking towards my grave. That was a rupture. A bending down so low that I will never be able to stand straight.”

Käthe Kollwitz, Diaries, 12 October 1917

The diaries also document her struggle to create a memorial for Peter. For years, she experimented with various forms and concepts, often feeling that no artistic expression could adequately convey the depth of her sorrow or the senselessness of his death. She wrote about her desire to create something that would not glorify war but rather mourn its victims. “I want to create something that will make people feel the pain of war, the pain of mothers who have lost their children,” she noted in her diary in 1919.

This long gestation period, spanning over a decade, underscores the profound emotional and artistic challenge she faced. The entries reveal her meticulous process of sketching, modelling, and discarding ideas, always striving for an authentic and universal expression of grief. She wrestled with the form, the material, and the message, constantly refining her vision.

The diaries are replete with descriptions of her attempts to capture the essence of parental grief, to distil it into a tangible form that would resonate with others. This iterative process, documented in her own words, provides a unique insight into the creative journey of an artist grappling with profound personal tragedy.

Her letters, particularly those exchanged with her husband, Karl, and close friends, further illuminate her emotional state and philosophical reflections on war and humanity. These correspondences reveal her growing pacifism and her unwavering belief in the power of art to foster empathy and understanding. She often expressed her hope that her work could contribute to a world where such senseless loss would never happen again.

The diaries and letters, therefore, are not just personal chronicles; they are powerful testimonies to the human spirit’s capacity for resilience and the transformative power of art in the face of adversity. They provide the essential context for understanding the emotional depth and profound significance of The Grieving Parents.

The Grieving Parents: A Legacy Etched in Stone

The Grieving Parents (also known as The Mourning Parents or The Parents) is arguably Käthe Kollwitz’s most poignant and enduring work. Conceived as a memorial to her son Peter, the sculpture took over a decade to complete, a testament to the profound emotional and artistic struggle involved in its creation. The sculpture, carved from Belgian granite, depicts two figures, a mother and a father, kneeling in silent despair.

The figures are monumental in their simplicity, their forms heavy with sorrow. The mother figure, representing Käthe Kollwitz, is wrapped in a shawl, her chin sunk into her chest, and her shoulders slumped, in contrast to her husband’s more upright posture. The father figure, modelled after Karl Kollwitz, is depicted with crossed arms, his face showing deep melancholy with downward-sloping lips and half-closed eyes that seem focused inward, suggesting a man locked in a prison of grief.

Both figures are kneeling, hugging themselves as if to ward off a palpable chill, symbolising enduring sorrow. The sculpture’s design emphasises the raw emotion of parental bereavement, devoid of patriotic sentiment often found in official war memorials. There is no overt display of emotion, no theatrical gestures; instead, the grief is internalised, etched into the very posture and form of the figures.

The choice of granite as a medium is significant. Its enduring nature reflects the permanence of grief, while its rough texture adds to the raw, unpolished emotion conveyed by the figures. The scale of the sculpture, larger than life, imbues it with a sense of solemnity and gravitas. The figures are not idealised; they are raw and human, their suffering palpable. This understated approach makes the sculpture all the more powerful, allowing viewers to project their own experiences of loss onto the universal figures.

Kollwitz deliberately avoided any heroic or nationalistic imagery, instead focusing on the universal human experience of loss. This decision was a radical departure from the prevailing war memorials of the time, which often glorified sacrifice and valour. The Grieving Parents stands in stark contrast, a quiet lament for the fallen, a powerful anti-war statement.

Käthe Kollwitz’s “The Grieving Parents” was first installed in 1932 at the Roggeveld Military Cemetery in Belgium. In 1954, the German graves, including Peter Kollwitz’s, and the memorial sculpture were moved from Roggeveld to the German war cemetery at Vladslo, Belgium, where “The Grieving Parents” remain today.

The cemetery is a sombre landscape, serving as a final resting place for more than 25,000 German soldiers. The sculpture’s placement, overlooking numerous flat granite stones—each bearing the names of twenty soldiers—establishes a poignant connection between art and remembrance. The figures of the grieving parents stand as eternal mourners, symbolising all parents who lost children in the war.

Their presence at the cemetery transforms it from a mere burial ground into a sacred space of collective mourning. The sculpture’s enduring power lies in its ability to transcend specific historical events and resonate with anyone who has experienced loss. It is a timeless testament to the devastating human cost of war and the enduring power of parental love and grief.

The “Grieving Parents” message of sorrow and remembrance deeply resonates with visitors from around the world. It serves as a sacred pilgrimage site for those seeking to comprehend the profound impact that the Great War and conflict, in general, have on individuals and families.

The Silent Stones of Vladslo: A Sombre Testament to Loss

The Vladslo German War Cemetery, located near Diksmuide in West Flanders, Belgium, is one of four German military cemeteries in the region, serving as the final resting place for 25,644 German soldiers who fell during World War I. The cemetery’s design is stark and sombre, reflecting the immense loss it commemorates. Unlike many Allied cemeteries with their pristine white headstones, Vladslo features rows of simple flat granite stones, often bearing the names of multiple soldiers. This design choice emphasises the collective nature of the sacrifice and the anonymity of many of the fallen, creating a powerful visual representation of the scale of human loss.

The overall impression is one of a “burial field of sacrificed and lost youth,” where the quiet ambience and the starkness of the massed graves evoke a powerful sense of the human cost of war. Visitors often describe it as a serene yet haunting place. The trees planted within the cemetery contribute to the melancholic atmosphere.

The cemetery’s history is deeply intertwined with the brutal trench warfare that characterised the Western Front. Many of the soldiers buried at Vladslo died during the First Battle of Ypres in 1914 and subsequent battles in the Yser Salient. The sheer number of graves is a stark reminder of the devastating impact of the war on a generation of young men.

As we look toward “Die Eltern” – The Parents, we are reminded of the solemn tribute represented by each stone, marking the final resting place of 20 young men. Each grave tells a story of unknown courage, sacrifice, and loss. War inevitably exacts a heavy price, depriving humanity of its brightest talents and potential.

The cemetery is meticulously maintained by the German War Graves Commission (Volksbund Deutsche Kriegsgräberfürsorge), an organisation dedicated to preserving the memory of German war dead and promoting reconciliation. Their work ensures that the sacrifices made are not forgotten and that future generations can learn from the past.

The presence of Käthe Kollwitz’s The Grieving Parents at Vladslo is central to the cemetery’s emotional resonance. The sculpture’s position serves as a focal point, immediately conveying the profound sorrow associated with the site. The figures face the graves, their silent vigil a perpetual lament for the fallen. The sculpture transforms the cemetery from a mere burial ground into a powerful memorial, a place where art and history converge to evoke deep empathy.

Visitors often leave flowers or small tokens at the base of the sculpture, a testament to its enduring power to connect with individual experiences of loss. The combination of the stark landscape, the countless graves, and Kollwitz’s deeply moving sculpture creates an unforgettable experience, prompting reflection on the universal tragedy of war and the enduring human need for peace. The cemetery, with The Grieving Parents at its heart, stands as a powerful reminder of the human cost of conflict and a poignant plea for reconciliation.

The Enduring Legacy: Art, Grief, and Pacifism

Käthe Kollwitz’s The Grieving Parents and her accompanying diaries and letters represent a profound artistic and personal response to the horrors of war. Her work transcends national boundaries and specific historical events, speaking to the universal experience of grief and loss. The sculpture, rooted in her personal tragedy, becomes a monument for all who have suffered the consequences of conflict. Its placement at the Vladslo German War Cemetery ensures its message of sorrow and remembrance continues to resonate with visitors from around the world.

Kollwitz’s artistic legacy is not merely about depicting suffering; it is about fostering empathy and advocating for peace. Her unwavering commitment to pacifism, born from her personal loss, is evident throughout her work. She believed that art had the power to awaken consciences and to challenge the glorification of war. The Grieving Parents stands as a powerful anti-war statement, a silent protest against the senseless destruction of human life. It is a testament to the enduring power of art to bear witness to human suffering and to inspire a longing for a more peaceful world.

The study of Kollwitz’s diaries and letters, in conjunction with her monumental sculpture, offers invaluable insights into the psychological impact of war on individuals and families. They reveal the long and arduous process of mourning, the search for meaning in the face of despair, and the transformative power of art as a means of processing trauma.

Her work remains relevant today, serving as a powerful reminder of the human cost of conflict and the importance of striving for peace. In a world on the brink of another global conflict, Kollwitz’s art provides a timeless warning about the horrors of war. Her legacy reminds us that even in the darkest times, art can illuminate the path toward understanding and reconciliation.

Photography Info: False colour infrared HDRs taken with a converted Nikon D70s in November 2011.

Fragmented Memory 🙂