Uncle Monty’s Crow Crag:

Wet Sleddale Reservoir near Shap is an artificial reservoir built to supply Manchester with fresh water. The Wet Sleddale Valley was said to be once owned by Shap Abbey. Being unfamiliar with this area, and out of curiosity, I decided to do a short circular walk around it on an overcast, dull, but dry February day.

The land is consistently boggy, and given it was February, the impression was of a bleak emptiness; it is not the most attractive place. Nevertheless, the day threw up a few surprises, one being Sleddale Hall; that unbeknownst to me then was Uncle Monty’s country cottage, Crow Crag, in the cult film Withnail and I.

Situated on a steep slope, Sleddale Hall has a commanding view over the reservoir. The setting, high on windswept, barren moorland, conveys an atmosphere akin to Wuthering Heights.

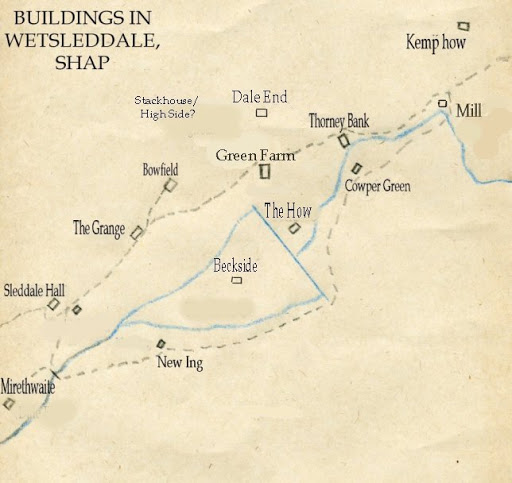

For such a substantial property, there is little known about its history. Originally it was named Sleddale Head and is thought to have been built in the early 18th century. Stone from the 17th century, however, has also been uncovered on the site. Like many farmsteads in Wet Sleddale, their origins remain obscure; nonetheless, Sleddale Grange has a date of 1691 above the door. Speculation suggests that farmsteads moved up the valley as the land became more viable.

The Shap Registers of 1746 and 1750 list Thomas and Katherine Graham as a residents at Sleddale Hall. The Hall was likely subdivided, and William Hawes of Shap was also living there between 1740 & 1758. An 1802 survey of Sleddale Hall and the surrounding land indicates it was part of Lowther Hall Farms.

The 1802 report stated:

‘Sleddale Hall is situated a few miles south westwards from Shap in a narrow valley among the mountains. We could find nothing to give us any information as to the quality of land in this farm. There is a considerable extent enclosed on each side of the vale which is at present singularly divided in to different fields. This we calculated to be about 250 acres, consisting partly of woodland, partly of poorish meadow ground, and partly of pasture, all of which, or nearly all, lies in rapid declivities.

Besides the above inclosed ground, there may be about 2,300 acres of barren mountains, forming altogether a tolerably good sheep farm. The meadow ground is mostly capable of improvement by draining, & that at a reasonable expense. This farm, every thing considered we suppose may be worth a rent of £150. But as observed before, our means of calculating the value were very defective.’

In 1829, Sleddale Hall was recorded as:

‘Sleddale Hall, now a farm-house belonging to C. Wilson, Esq., was long the seat of the ancient family of Sleddale, one of whom was the first Mayor of Kendal, and possessed Gillthwaite-Rigg, and some other estates.’

The Harrison family occupied Sleddale Hall in the 1940s. At some point, Manchester Corporation Waterworks, which subsequently became United Utilities, acquired the property. In the 1960s, work began on the construction of the reservoir. In 2009 Tim Ellis, an architect from Canterbury in Kent and a fan of the cult film Withnail and I, bought it from United Utilities. The Hall had been unoccupied for many years at this point and was falling into disrepair.

Tim Ellis said: ‘I first saw the film about seven years ago and have been a fan ever since. I would like to restore the building in a way that other fans of the film could approve of. There is a lot of work to be done before I can draw up firm plans but my intention is not to deprive Sleddale’s many admirers of its links with its iconic past.’

The film Withnail and I; was released in 1987. For some reason, I must have been living under a rock as I had never heard of it until researching Sleddale Hall. Now, after having watched it, I can understand its cult status.

Withnail and I/Film synopsis:

Two out-of-work actors — the anxious, luckless Marwood (Paul McGann) and his acerbic, alcoholic friend, Withnail (Richard E. Grant) — spend their days drifting between their squalid flat, the unemployment office and the pub. When they take a holiday “by mistake” at the country house of Withnail’s flamboyantly gay uncle, Monty (Richard Griffiths), they encounter the unpleasant side of the English countryside: tedium, terrifying locals and torrential rain.

I passed a quaint packhorse bridge, on the route up to the hall, built over a narrow rocky beck. In the movie, Withnail and Marwood can be seen comically fishing with a shotgun here.

Sleddale Hall sits on quite a steep slope with some aptly named hills behind it: Bleak Hill and Willy Winder. From there, you can head over to Haweswater.

The Davis family | Bowfield Wet Sleddale:

Another point of interest was Bowfield, of which only the barn now exists. I cannot say exactly what drew me to this building, but it has a tale to tell.

In Whiteside’s book ‘Shappe in Bygone Days’ 1904, Bowfield is mentioned:

Occupied by Downing. At Bowfield in “t’other -place,” i.e., not the kitchen, but the parlour, is a small oak cupboard in the right of the fireplace, with one panel and one drawer, which has on it: E H E 1703. Outside the front, is a small window that may have been moved from an older house when this one was built. But this house, which has oak beams all through, looks older than 1703. In the front are eight two-light windows and two-one-light.

There are census returns from 1851. In 1901, it was named Bow House. If only walls could talk, what tales they would tell of bygone days. In 190,1 the census tells us the following:

1901 – Bow House

Anthony Davis, Head, marr, aged 40, shepherd, worker, born Ashby, Westmorland.

Hannah Davis, wife, marr, aged 45, born Shap, Westmorland.

John Davis, son, single, aged 13, born ditto.

Frances Davis, daughter, aged 11, born ditto.

Anthony Davis, son, aged 9, born ditto.

George Davis, son, aged 7, born ditto.

William Davis, son, aged 4, born ditto.

Hannah Davis, daughter, aged 1, born ditto.

It is hard to believe the austerity of our ancestors’ lives only a few generations ago. It would, however, put them in good stead for the winds of war soon approaching. The armageddon of the Great War would rear its ugly head 13 years after this census. Being a period of interest to me, I researched to see if any of the young boys had gone to war. Up until January 1918, at least three of the four boys had joined up.

Hidden Valour:

A Newspaper report in September 1917 tells us the following:

‘Private Anthony Davis, Border Regiment, son of Mr. Davis Wet Sleddale, Shap, is in hospital at Portsmouth, suffering from severe wounds in the legs. He was wounded in a trench in France by a shell, and almost buried among the debris. After being liberated he was attended to by a sergeant, and then placed on a stretcher and carried four miles to a motor ambulance, which conveyed him to a hospital. Private Davis has two older brothers serving in France.’

The Penrith Observer printed in January 1918 the following:

‘Private William Davis Border Regiment, son of Mr. A. Davies, Wet Sleddale, has been awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal for Bravery in France. Mr Davies has three sons in the army two of them have been in home hospitals suffering from wounds received in action. The eldest son, Sergeant John Davies Border Regiment, was so severely wounded in the left arm that the limb had to be amputated at the shoulder this week. The other man Private Anthony Davis is in hospital in Hants suffering from shrapnel wounds in the thigh.’

Distinguished Conduct Medal:

Thanks to Craig at the Great War Forum for the DCM citation:

26232 L./C. W. Davis, M.G.C (104 company Machine Gun Corps), London Gazette 4th March 1918.

‘For Conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty. He was in charge of a machine gun team on the flank of a newly captured postion. Though his gun was several times buried by shells he kept it in working order, rallied his shaken team, and did valuable work in repelling several counter-attacks, inflicting heavy casualties on the enemy. He showed splendid determination and coolness.’

How would the absence of three sons impact the Davis family’s ability to work and feed themselves? How did John Davies, the 13-year-old boy in the 1901 census, cope post-war without the use of an arm? And what of Anthony Davis, the 9-year-old from the 1901 census, buried alive and severely injured in the legs?

Unfortunately, I cannot answer all these questions. Nevertheless, I have uncovered that Anthony transferred to the Labour Corps; the severity of his injuries made him unfit for service in a fighting unit. Although lacking in prestige, service conditions in the Labour Corps were more often than not physically demanding and dangerous. The injuries Anthony suffered during the war appear to have contributed to his death in August 1920. He lies in St. Michael‘s Churchyard, Shap, beneath a military headstone engraved with the cap badge of the Border Regiment.

May He Rest In Peace:

The inscription at the base of his headstone, requested by his mother, reads: ‘May He Rest In Peace’. The inscription, originating on Christian gravestones from the 8th Century, is very common. I suspect, however, that his mother truly felt that such were his mental and physical injuries, that only in death would her son find peace.

Aftermath:

The real forgotten story of the Great War is the aftermath. Some returned home; some did not. But all families throughout the British Isles had to move on, regardless of the difficulties. These stories of stoicism in the face of massive hardship are sadly missing from history. These resilient, hard-working people did what they did best: kept silent and made the best of what they had. A lesson we modern pampered generations could do well to emulate.

While Sleddale Hall is of evident interest, I have found the now Bowfield Barn even more intriguing. The walls of Bowfield hide tales that even the greatest authors of classic literature would have struggled to conceive. Maybe why, as I walked the track out to Green Farm, I would often stop and look back to ponder what lives and stories unfolded there.

Wet Sleddale was never the same after the Great War. Change to Wet Sleddale as the decades marched on was inescapable. The Reservoir was the death knell. Not only was the community gone, but the physical structure of the valley was also changed forever. Time has swept those days from living memory. All that is left are the ruins and ghostly echoes of what once was.

#LakeDistrictPhotographyWalks

For anyone interested in more info on Sleddale Hall check this website out.

The website is self-funded, and my work is free. All profits from the sites product links go to SightSavers;if you have enjoyed any aspect of this site please consider a giving a donation here. No one should go blind from avoidable causes. How many people’s sight will you help us save today?

Fragmented Memory 🙂

Hello. I was interested to read your article. I thought you may be interested to see a photo I have of Bowfield – the house was attached to the South end of the barn; the barn survives but it was not part of the house. If you send me an email, I’d be happy to forward the photo I have to you.

Thank you for this article and the pictures, in particular thanks to Tim Ellis for the Bowfield photo. My ancestors Joseph and Ann Abbott were recorded as living at Bowfield Cottage in the 1851 census when Joseph was recorded as a farmer of 35 acres. Only 1 of their 4 children reached adulthood.

Thanks for the comment Pauline. Tough times!